What is an Old Irish Goat?

The Old Irish Goat is Ireland’s indigenous, landrace breed of goat. The term “landrace” refers here to the fact that the breed has been naturally shaped by the Irish landscape and climate since its arrival, approximately 5,000 years ago, in the Neolithic Age. This has resulted in a highly adapted, cold weather, small and stocky goat with short, strong legs and a deep body to accommodate large quantities of nutritionally poor forage. The head, adorned with impressively large horns, is delicately shaped with a dished facial profile and long muzzle that serves to warm the air before entering the lungs. The ears are small in size to protect against frostbite and are worn in a pricked position. Coats come in a varied range of up to twelve colour patterns that blend with the landscape and are typically long, course, thick and “act as a natural thatch” with an under-wool of cashmere that pushes the hair outwards in Winter.

What is the history of the Old Irish Goat?

The Old Irish Goat epitomises the impoverished and pastoral history of Ireland. The breed dates from the same era as famous Irish Neolithic monuments including the Céide Fields in County Mayo, the Megalithic Chamber Tomb, Bru na Bóinne in County Meath and Poulnabrone Portal Dolman in the Burren, County Clare.

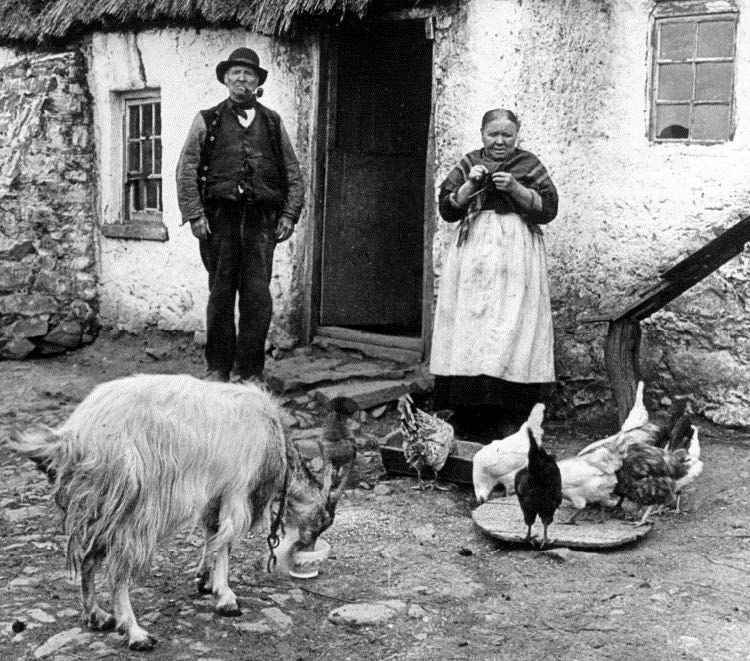

Known historically as “the poor man’s cow”, the goat was, by virtue of its hardiness, a crucial component of Ireland’s past farming and rural life. Indeed, this breed ensured the survival of Ireland’s earliest settlers and whole village communities, it also helped some families stave of starvation when potato crops repeatedly failed. The Old Irish Goat is deservedly celebrated in Irish folklore, tradition, paintings and literature.

Does the Old Irish Goat still exist?

We know that the Old Irish Goat still exists in feral herds as a rare breed that is facing extinction, although we do not know how many still survive.

Why is the Old Irish Goat facing extinction?

The Old Irish Goat was once a ubiquitous character of the traditional Irish farmstead and during the Nineteenth Century Irish goats were exported in large numbers to England, Scotland and Wales, from the ¼ million strong population.

The tradition of exporting Old Irish Goats to England, Scotland and Wales had a strong association with the Newry Mourne, Slieve Gullion region of Northern Ireland, with drovers travelling to the west of Ireland to purchase Old Irish Goats and then droving them through market towns across Ireland, England, Scotland and Wales. With local historian Michael Murphy referring to the drovers as,

“the Goat-Men of South Armagh”.

Then, around 1900, the process was reversed and Ireland witnessed its first importation of ‘improved’ dairy goats. The idea being to take the Old Irish goat in hand and “improve” it by the use of dairy breed stud goats. Since then the Irish goat has been the subject of a chronic spiral of decline driven by changes in agricultural practices, cross breeding with modern improved goats, casual hunting and indiscriminate culls of feral herds. All made worse by a lack of recognition, leading to a relentless mongrelisation of the old type towards more nondescript individuals and a declining population.

Why conserve the Old Irish Goat?

The plight of the Old Irish Goat serves as an indicator to an acknowledged low priority in the modern world attached to rapidly diminishing genetic variability in our food sources.

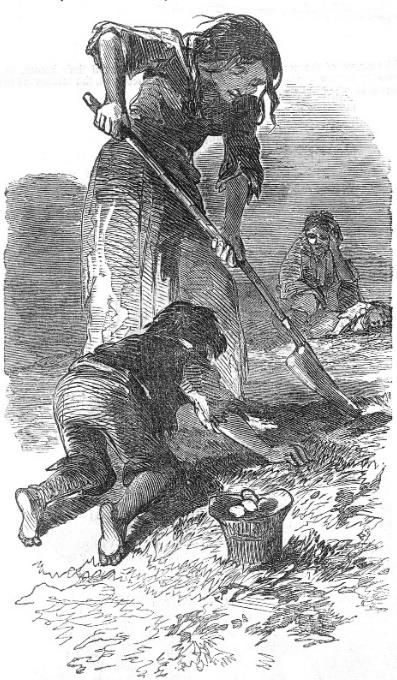

The Irish potato famine, known as “The Great Hunger”, is the event from history that reminds us of the dangers of this path. A central factor in this catastrophe being the reliance on a single plant variety, the Irish Lumper potato, which was susceptible to blight.

Modern farming methods tend to focus on particular strains of animal breeds and plant varieties. Of the 8,300 animal breeds known, 8% are now extinct, 22% are at risk of extinction and 6 breeds are lost each month. These trends prompted the Food and Agricultural Organisation of the United Nations to advise in 2009 that:

“Animal genetic resources are among the most valuable and strategically important assets a country possesses, they are the animal breeder’s raw material and among the farmer’s most essential inputs.”

In addition, the Old Irish Goat is a unique and untapped artisan food, conservation grazing, heritage and tourism resource. The Old Irish Goat is a diminutive, resilient and charismatic creature, that is living, breathing history and representative of our cultural and pastoral heritage.

International Calls for Conservation

Calls for conservation began almost a century ago when Walter Paget, wrote eloquently of the Old Irish Goat in 1918:

“The Irish goat in the process of time has developed a coat which acts as a natural thatch in the moist humid atmosphere of its native districts, and to graft Nubian or Swiss blood into this breed does not add to its beauty, and, to our mind, impairs its usefulness. The Irish goat, we maintain, is the best we have for the purpose, and it should be kept pure in type.”

Walter Paget

The 1992 Rio Earth Summit, under Agenda 21, Chapter 14, states that;

“Some local animal breeds, in addition to their socio-cultural value, have unique attributes for adaptation, disease resistance and specific uses and should be preserved. These local breeds are threatened by extinction as a result of the introduction of exotic breeds”.

The 1992 Convention on Biological Diversity calls for conservation under the Precautionary Principle: –

“if there is a threat of significant loss of biological diversity, lack of scientific certainty should not be used as a reason for postponing measures to avoid or minimise such a threat”.

The 2007, Interlaken Declaration, states that: –

“The sustainable use, development and conservation of animal genetic resources for food and agriculture makes an essential contribution to facilitating the implementation of Agenda 21 and the Convention on Biological Diversity.”

In 2009, the Food and Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations cautioned that: –

“The flourishing of intensive livestock production systems which utilize a narrow range of breeds has contributed to the degradation of the animal genetic resources and the marginalization of the traditional livestock production ones, leading many breeds to a risk of disappearance. So far, the greatest loss of genetic resources occurs in Europe with 16 out of the 19 extinct goat breeds worldwide”.

And in 2009, historian, Ray Werner, proposed that the little known or remembered Old Irish Goat might still exist: –

“there is a very compelling and urgent need to preserve the Old Irish Goat breed as a genetic and cultural resource. It is the ancient breed of the nation, and the symbol of its past.”

Ray Werner

Is there national protection for the Old Irish Goat?

No, while the ancient inanimate tombs of Ireland, such as Céide Fields, Poulnabrone and Bru na Bóinne are protected under Irish law, our living heritage breeds are not. Neither the Heritage or Wildlife Acts afford protection to the Old Irish Goat, this ironic situation is referred to by the society as “the King Puc Paradox”.

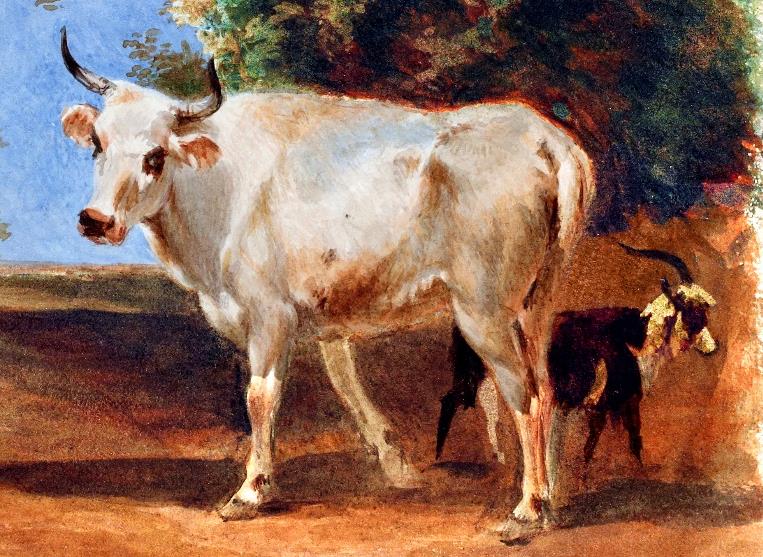

Ireland’s Lost Indigenous Breeds

It is likely that the once revered Old Irish Cow was still to be found in Ireland during the Middle Ages and we know that individuals cropped up during the Nineteenth Century, however today it is extinct.

According to Mason’s, Dictionary of Livestock breeds, published in 2002, the Cladoir sheep was native to Connemara. Mason placed this breed in the Northern Short-tailed group and added that it was polled and occasionally coloured. Alternative names are the “Cladagh” or ‘Cottagh’, meaning ‘shore’, this being in keeping with the fact that the Cladoir was also known as ‘The Coastal Sheep’. The Cladoir is now technically extinct, being found only as a crossbred.

Proving the existence of Ireland’s “Lost Goat”

There is no precedent or template for saving an indigenous breed from feral stock in Ireland or the UK. In attempting to prevent the Old Irish Goat becoming another lost Irish breed, the Society would first have to prove it still exists!

The society was faced with a complete absence of physical measurements, DNA or readily accessible animals, since the surviving Old Irish Goats were believed to exist in remote mountain ranges. The society would also need to compare living Old Irish Goats against primitive goats from the early 1900’s, predating the importation of modern breeds.

To “travel back in time” the society looked to the “Dead Zoos” of Ireland, Scotland, England and Wales and their collections of goat bones and skins for DNA and to old taxidermy specimens, sketches, paintings and pictures for clues as to the characteristics of Ireland’s “Lost Goat”.

Ancient goat specimens were DNA profiled and compared to selected living feral goats from Mulranny, in County Mayo. The initial and foundational Old Irish Goat DNA study, carried out in collaboration with Trinity College Dublin School of Genetics, was published in the Biology Letters, Royal Society Journal. This peer-reviewed journal publishes highly innovative, cutting-edge research and confirms the Old Irish Goat as a distinct, indigenous, heritage breed, deserving of further conservation and research efforts: “Overall, these findings identify Mulranny goats as some of the last modern representatives of the ‘Old Irish’ type of goat, once ubiquitous throughout the island, and highlight them for much needed conservation efforts.”

A second DNA study found Old Irish Goats from the Burren to have “distinct variation from other breeds” [British Alpine, Toggenburg and Sannen] Quaid et al (2014). The Old Irish Goat Society participated in the ‘ADAPT (adaptation) Map’ initiative, to genome sequence global goat populations. DNA analysis confirmed that the Old Irish Goat is clearly differentiated from improved Swiss and primitive European (Icelandic, Dutch and Norwegian) breeds and that primitive Irish and English (i.e. Cheviot and Bagot) breeds, while separated for some time, are still closely related within the Atlanto-Scandinavian Breed Group. Further investigation is required into the latter and possible influential factors, such as the exportation of goats from Ireland to England, Scotland and Wales around the turn of the 20th Century.

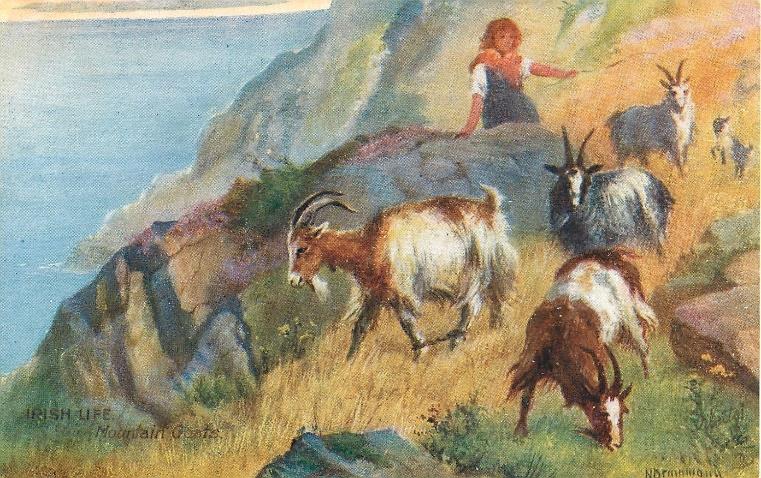

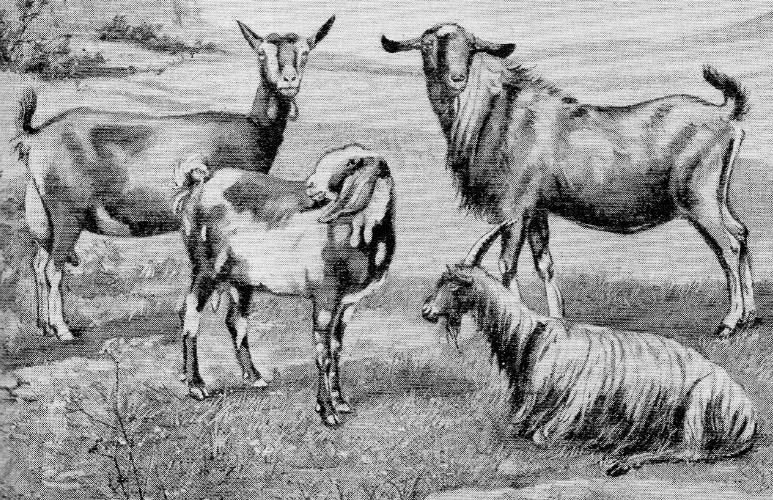

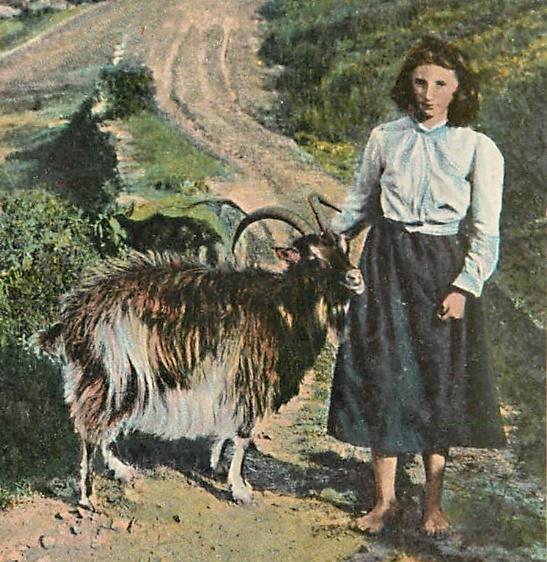

In addition to DNA evidence, old sketches paintings, postcards and reference books identify the Old Irish Goat, with remarkable continuity, as a multi coloured goat with small pricked ears, long coat and large horns. Mason’s, World Dictionary of Livestock Breeds states “The Old Irish Goat is a long haired goat breed found in Ireland… in white, black and grey… used for both meat and milk” The encyclopedia entitled “The Book of Knowledge,” c1895 includes a defining sketch, referring to “Goats: some of the popular breeds, from left to right: Toggenburg (Swiss) Nubian, Anglo-Nubian, and Irish (long-haired)”

The “Connemara Goat Girl” painting from 1880 shows the female Old Irish Goat with small, pricked ears and long coat.

The postcard “Mountain Goat among the Scottish Lochs”, from c. 1904, with echoes of the Connemara Goat Girl, showing a remarkable continuity of type between the primitive Old Scotch Goat and a modern day female Old Irish Goat from Connemara.

The Connemara female below is an exceptional example of the ‘long-coated’ Old Irish Goat with Bezoar colour pattern.

Is the Old Irish Goat a distinct breed?

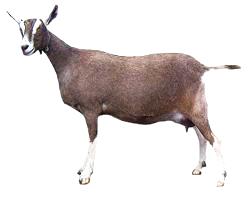

Historic and DNA evidence support the view that the Old Irish Goat is a distinct unimproved landrace breed, very different to the standardized dairy Anglo-Swiss breeds. In comparison with the Old Irish, breeds like the British Saanen, British Toggenburg and British Alpine are huge, a large male British Saanen standing 10 inches taller and weighing half as much again as the largest Old Irish male.

Modern Swiss and British improved breeds have a characteristic wedge shape, long neck, short coat, are hornless and tasselled.

By contrast, the Old Irish goat is almost diminutive, quite square and symmetrical in outline, noticeably bearded and with an unruly hairy hearthrug look to it. Its ears are small and dinky, horns impressively large and facial outline dished and quite delicate. Lastly, the individual dairy breeds are identifiable by a particular colour, this being a defining feature, whereas the Old Irish goat is multi-coloured, with a herd looking like a moving patchwork quilt.

Can the Old Irish Goat be saved from extinction?

The Old Irish Goat has become feral or wild and therefore capture and breeding is exceptionally challenging and requires ardent hill farming skills along with special handling facilities, daily animal husbandry along with hand rearing of kids and specialist knowledge on genetics.

However, despite these challenges the Old Irish Goat Society is honouring the Precautionary Principle, with a pilot captive breeding program that aims to save vital genetic resources and assess the challenges of re-domesticating the breed.

The new born kid carries forward vital genes from a beautiful Grey Pied, Old Irish Goat, which at 15 years is reaching the end of her breeding life. The small head size of the kid goat allows it to rise to its feet quickly after birth.

Outlook

Saving the Old Irish Goat from extinction remains a formidable challenge. To achieve international “Endangered Stable” status requires 1,000 Old Irish Goats to be registered. Within this population there are 12 colour patterns and several physical characteristics to be conserved.

Achieving this, would make a timely contribution, by Ireland, to the EU target of “Halting the loss of biodiversity by 2020” and the United Nations Sustainability Development Goal 15: “Life on the Land: Halt biodiversity Loss”.

The future of the Old Irish Goat requires a concerted effort by the society, the state, interest groups and citizens. It is difficult to reassure the reader as there are limited conservation resources available to save what is a rare breed that is already extinct in domestication. For more information or options to help contact the Society via our website.

Acknowledgements

The Old Irish Goat Society gratefully acknowledges the support and assistance toward research and conservation of the Old Irish Goat provided by the following:

Gift of Hands – Mulranny

Essence of Mulranny Studio

Rescue & Conservation of Endangered Breeds Utah, USA

The Department of Agriculture, Food and the Marine Agricultural Genetic Resources Committee

South West Mayo Development Company

Mayo, Galway and Longford County Councils

The Heritage Council

The Smurfit Genetic Institute, Trinity College Dublin

Weatherbys DNA Laboratory

University College Dublin

The Natural Museums of Dublin, London, Scotland, Wales and the Isle of Man

The American Ireland Fund

The Western People

Text by Seán Carolan, Ray Werner and Maeve Foran

Image acknowledgements as per appearance

Cover, 17. Pam Gray

1. Ray Werner

2, 6, 7, 15. Unknown

3. Mountain Goats, Ireland – Nora Drummond (1862 – 1949)

4. http://www.maggieblanck.com/

5. Library of Congress USA

8, 12. The National Gallery of Ireland

9. Tom King

10. National Museum of Scotland

11. The “The Book of Knowledge” encyclopaedia

13. Postcard Irish Peasant Life Series Raphael Tuck & Sons

14, 17. Seán Carolan

18. Eamon McCarthy – Images of Mayo

Funded by Mayo County Council under Local Agenda 21. Published: June-2017

Contact Us

Website: www.oldirishgoatsociety.com

Email: [email protected]

Address: the Old Irish Goat Centre, Mulranny, Co. Mayo.